Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

People with favorable socioeconomic conditions, such as high incomes or education levels, face a reduced risk of age-related diseases and show fewer signs of biological aging than peers of the same age, finds a new study led by University College London (UCL) researchers.

Social inequalities appear to have a direct impact on the biological aging process, according to the authors of the Nature Medicine paper.

The scientists found that people with more social advantages had fewer proteins in their blood that are linked to the aging process, including those connected to inflammation and the immune system.

This study provides strong biological evidence that social conditions influence the pace of aging. For decades, we’ve known that social advantage is linked to better health, but our findings suggest it may also slow down the aging process itself.

Our study highlights that healthy aging is an achievable goal for society as a whole, as it is already a reality for people with favorable socioeconomic conditions.”

Mika Kivimaki, Lead Author, Professor, UCL Faculty of Brain Sciences

The study is based on four large longitudinal studies that have been tracking their participants for many years: the Whitehall II study in the UK (which is led by Professor Kivimaki as Director), the UK Biobank, the Finnish Public Sector Study (FPS), and the Atherosclerosis in Communities (ARIC) study in the US. Together, these studies include over 800,000 participants.

The measures of social advantage included both early-life factors, such as education and father’s socioeconomic position, and adulthood indicators such as neighbourhood deprivation, occupational status, or household income.

The markers of aging were measured by diagnoses for diseases known to be linked to aging, and by blood tests measuring proteins circulating in the blood’s plasma, in a measurement called advanced plasma proteomics. Many proteins are known to impact the aging process, while aging also impacts the mix of proteins in the blood, so protein counts can reflect multiple age-related processes that may be occurring before the onset of any diseases.

Disease outcomes were determined over 10 years after the measures of social advantage for two of the cohorts, and over 20 years later for the Whitehall II and ARIC cohorts, to discover if early or mid-life social factors contributed to aging many years later.

The researchers found that the risk of 66 age-related diseases was affected by social advantage. Averaged across the list of diseases, there was a 20% higher risk of disease for people with low socioeconomic status relative to high socioeconomic status, while after 15 years, those with low socioeconomic status had a similar number of age-related disease diagnoses as those in the high socioeconomic status group did after 20 years.

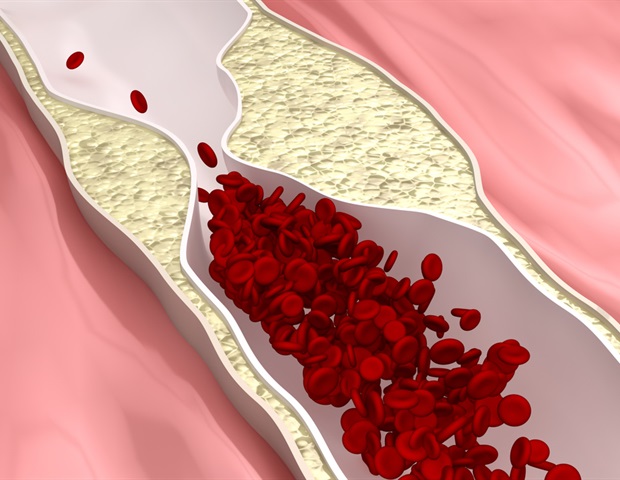

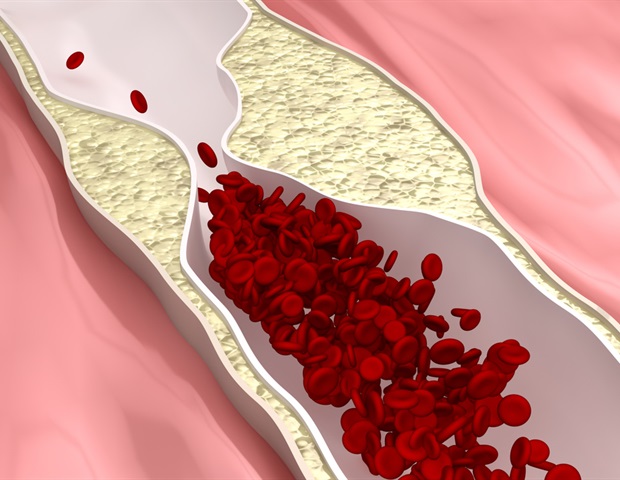

For some diseases, including type 2 diabetes, liver disease, heart disease, lung cancer and stroke, the risk was more than twice as high in the most disadvantaged group relative to the most advantaged.

The scientists found that levels of 14 plasma proteins were affected by socioeconomic advantage, including proteins known to regulate inflammatory and cellular stress responses. The researchers estimated that up to 39% of the reduced disease risk in socioeconomically advantaged people may be influenced by these proteins.

Co-author Professor Tony Wyss-Coray (Stanford University) explained: “aging is reflected in the makeup of proteins in our blood, which includes thousands of circulating proteins linked to biological aging processes across multiple organ systems. These biomarkers are indicators of health that enable us to assess how social differences can dictate the pace of aging.”

The researchers found evidence that changes to social standing can have a measurable impact on biological aging, as people who progressed from low levels of education early in life to middling or high social advantage later in life had more favorable protein concentrations relative to those whose circumstances had not improved.

The researchers say that more research is needed to elucidate how exactly social factors can impact biological aging.

Co-author Professor Dame Linda Partridge (UCL Institute of Healthy aging) explained: “While our study does not tell us why social advantage can slow the aging process, other studies have suggested that it may be related to factors such as life stress, mental health, exposure to pollution or toxins, and behaviours such as smoking, drug and alcohol use, diet and exercise, as well as access to medical screenings, check-ups, vaccinations and medications.”

Another recent study led by the same researchers, published last month, found that a blood test determining how much our organs have aged could predict the risk of age-related diseases decades in advance, which could help with preventative medicine for people showing signs of accelerated aging.

Professor Kivimaki added: “Blood tests are able to pick up on signs of accelerated aging, which could help us to determine who would likely benefit from targeted interventions to improve their health as they age.”

This study was supported by Wellcome, the Medical Research Council, the US National Institutes of Health, and the Research Council of Finland.

Source:

University College London

Journal reference:

Kivimäki, M., et al. (2025). Social disadvantage accelerates aging. Nature Medicine. doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03563-4.